Ty Longley marched to the beat of a different drummer, said his mother, Mary Pat Fredericksen.

Ty Longley marched to the beat of a different drummer, said his mother, Mary Pat Fredericksen.

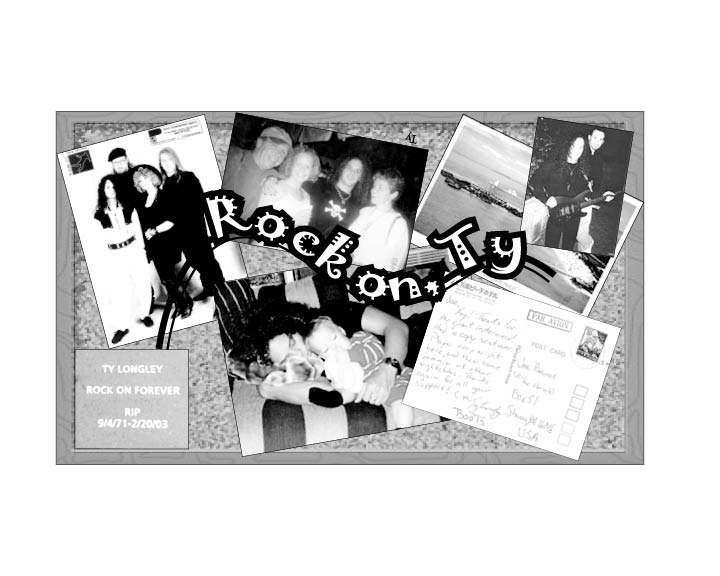

Which is odd, considering Longley, formerly of Brookfield, was a guitarist. That’s just one of the things that was different about Longley, who died 15 years ago in the fire at the Station nightclub in West Warwick, R.I. at age 31.

“You never knew what was coming out of that mouth, and that’s why he was so lovable,” said Fredericksen, of Sharpsville. “He’s like me – he loved shock value. I’m going to say he definitely got my sense of humor. It gets us through the worst of times and the best of times.”

Looking back, Fredericksen and her daughter, Audrey Dinger, said Longley’s humor is at the top of the list of things they remember about him. He would pull any number of pranks, from broadcasting fake messages on the public address phones in department stores to dressing up as a woman and slow dancing with men in clubs.

Even when he had a job as a telemarketer, he’d pull prank phone calls ala the Jerky Boys while he was on duty.

“He did some strange things and he never apologized for anything he did because he was doing what he wanted to do,” Fredericksen said.

When it came to music, however, Longley was serious. He would practice guitar constantly, playing himself to sleep at night.

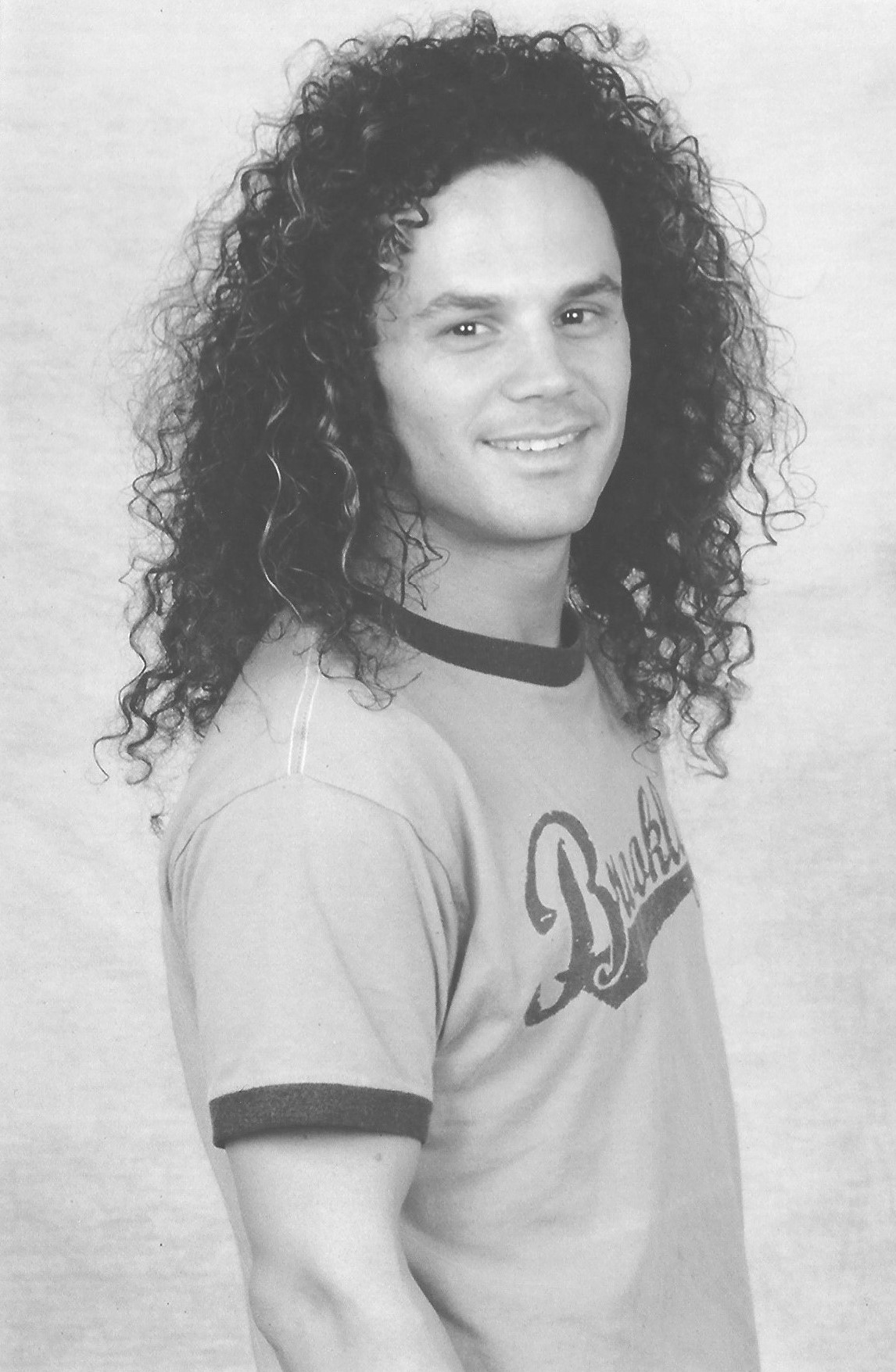

When Longley, who was known for his black, curly hair, was 8 or 9 years old, the family was staying in Geneva-on-the-Lake and Fredericksen and her son were walking on the beach. They could hear a band playing the Great White song “Rock Me” at a club.

“Ty says, ‘I’m going to play like that some day,’” his mother recalled. “We walked in and that music shook the place and he was just thunderstruck. I’ll never forget that day.”

Longley ended up playing with Great White, but not before a circuitous musical route that took him all over the world. He played in local bands Naked Alibi and Typhoon; toured midwestern motels with Scene of the Crime; entertained Japanese rock fanatics with Seduction; rocked American troops stationed in South Korea in Upper Level; and strummed lighter, poppier music with Lisa St. Ann.

The Great White gig came about after one of heroes, guitarist Mark Kendall, left the band. Kendall returned, playing alongside Longley, by the time the band had booked a gig for Feb. 20, 2003, at the Station. The band’s pyrotechnics ignited foam on the club’s walls and ceilings. One hundred people died in the fast-spreading fire, and another 200 were injured.

“It does, but it doesn’t, to me” seem like it’s been 15 years, Dinger said. “It seems forever that we’ve seen him, but time has flown.”

News stories on fires, concerts and certain songs that are played on the radio all make Dinger mindful of her brother.

“You can be driving and you just, for some reason, get a scent of him,” she said. “It just makes you think, ‘He’s here.’”

Looking back, the month before he passed away was a strange time for his family.

“It was like, he was being prepared,” Dinger said.

Longley gave Dinger away at her Las Vegas wedding, and it was so much more difficult letting him go when he had to leave, she said. Then, he fulfilled a lifetime dream of visiting Hawaii, and spent two weeks in Georgia with his mom, who lived there at the time.

“It was like two little girls,” Fredericksen said. “Playing and shopping, getting our nails done.”

“This is very, very morbid but, when he was with me those two weeks, I was playing with his hair and stuff and I said, ‘I just know he’s not going to grow old,’” she said.

On the ride to Florida, where Longley was resuming touring with Great White, “we were talking about his childhood and just things that we’d never talked about,” Fredericksen said. “When he got out of the car, he said, ‘Thank you, mummy.’ Just, ‘Thank you.’ And he walked away. I watched him play that night and it was great but he was kind of clingy. ‘Why don’t you come down to,’ somewhere in Florida? ‘Why don’t you come with us? Follow us down.’”

He also caught up with his dad, Pat Longley, in Detroit when Great White hit the Motor City.

“He had time with each of us separately,” Dinger said.

Fredericksen has visited the Station Fire Memorial Park and found it “very beautiful, very breathtaking” with its memorial stones for each victim and an angel statue in honor of the firefighters who responded.

“Up on the front of the whole place is a timeline of everything that happened and I couldn’t read it,” she said. “I started to and I said, ‘No, I don’t want to know this.’”

In addition to his parents, sister and a nation that grieved the loss of what was supposed to be the innocence of a rock ‘n’ roll concert, Longley left behind a niece, Macie, whom he adored, and a son, Acey, who was born after Longley died.

“Sometimes, it takes my breath away,” Fredericksen said of her son’s death. “Other times, I go, ‘I was so honored to have him in my life.’ You cry because you miss him, and you smile because you had him.”