Part of the Brookfield Township historical timeline at the Brookfield administration building.

There is little documentation of the Underground Railroad, the movement in which slaves escaped their owners and migrated to friendly territories, whether it be northern states that had outlawed slavery, Canada, Mexico or the United States’ undeveloped western territories, said Traci Manning, curator of education for the Mahoning Valley Historical Society.

It’s entirely understandable that people were hesitant to keep notes, logs and other written documentation of the activities of the Underground Railroad, she said in a public presentation for the Brookfield Historical Society on Dec. 9.

“If you told somebody about it (helping escaping slaves), you could literally be putting your life in danger,” Manning said. “No one is out there going, ‘My house is a station,’ and no one’s writing it down, either. No one’s making a journal saying, ‘We had four folks come through today, and I sent them off to Ashtabula.’ If that gets found, you’re easily going to jail, or you might be killed for it.”

That’s why first-hand accounts of former slaves who wrote their own stories or passed them on to historians, such as the Federal Writers’ Project of the 1930s, are so important, she said.

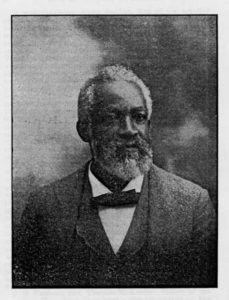

Charles Garlick

Charles Garlick, who escaped from slavery in 1843, wrote in his autobiography published in 1902 that his meandering path to freedom included a “tramp” from western Pennsylvania to Brookfield, where he was sheltered by Amos Chews. He spent one night in town before moving to Hartford and working for two weeks in a cheese warehouse owned by Ralph Plumb and Seth Hayes.

It’s also documented that Ambrose Hart, who built his home on the south side of Warren Sharon Road and the west side of Route 7, became president of the Trumbull County Anti-Slavery Society in 1838. His home – now called the Obermiyer house after a subsequent owner – and at least two others in Brookfield Center were stations on the Underground Railroad. Hart is attributed with helping about 60 people.

“We have a great history of what’s happening right here in Brookfield,” Manning said.

Ohio became an important pathway to freedom with the Ohio River, which also bordered slave states Kentucky and Virginia, at its southern border, and Canada at its northern. Escaping slaves could find passage across Lake Erie at port cities such as Ashtabula and Conneaut, she said.

Trumbull County had about 150 miles of Underground Railroad routes, “making it easily the largest network in Ohio,” Manning said.

Traci Manning of the Mahoning Valley Historical Society offers a program on the Underground Railroad for the Brookfield Township Historical Society.

Those routes shifted as need be, particularly after the 1850 passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed slave catchers to reclaim escaped slaves in the north. Some used that power to capture legally freed blacks and make them slaves.

“This is the worst law ever signed into law in America,” Manning said. “It gives slave catchers more power than God. The text of this law is basically saying that power is coming from God, that there is a higher power in the white population, and they have this kind of divine authority to enslave the African population.”

The law’s effect was felt in Brookfield.

“There are stories from right here, on the ground we are on right now, of slave catchers coming into town, looking for people, setting the dogs after their scent,” Manning said. “They’re just absolutely horrific stories.”

@@@

Brookfield Historical Society will present a program on historic homes at 7 p.m. Jan. 13 in the Briceland Funeral Service building, 379 Route 7, Brookfield.